This blog article explains how the pandemic challenged the foundations of the work which underpins my PhD research, and how there could be some useful new digital opportunities for researching biographical accounts of the past, present and future.

By Aled Singleton, November 2021

In October 2021 I started an ESRC-funded postdoctoral project in human geography at Swansea University. The work focuses on the environment in which the UK’s ageing population (born between the late 1940s and early 1960s) grew up: spaces including semi-detached houses, cul-de-sacs, out of town industry, and shopping centres.

I developed an interest in this broad subject through my PhD research at the Centre for Innovative Ageing at Swansea University. The empirical element of my work in 2019 included two interviewing techniques: (1) walks of the mind as face-to-face indoor conversations; and (2) outdoor walking or go along interviews, where the interviewee accompanies research participant(s) as they discuss and respond to the environment in which they find themselves.

These two techniques provided unexpected and deep insights into how people experienced everyday life in the past, ranging from the 1920s through to the present day. The first technique is useful for people who have limited mobility, and it worked well with one person who had dementia. I also like to work with artists to make site-specific indoor and outdoor public performances as a way of assembling and making sense of the underlying story.

This methodology of considering past, present and future is important (see more from Sarah Marie Hall’s Oral Histories and Futures work) when the interviewer may be many decades younger than the interviewee. Looking to the future, as we all age, the method could be useful for understanding the lives of people who are much younger than us.

Responding the pandemic in 2020: taking the method online?

Many of us were restricted in our movements in autumn 2020; and this influenced my thinking as I wrote the evaluation chapter of my PhD. The outdoor walking interviews would still be possible, albeit with some modifications to maintain distancing – some useful new resources from the National Centre for Research Methods. However, the walk of the mind – a sat-down experience using geographical references like maps and images to navigate through memories and emotions – would be a lot harder if you can’t easily share space.

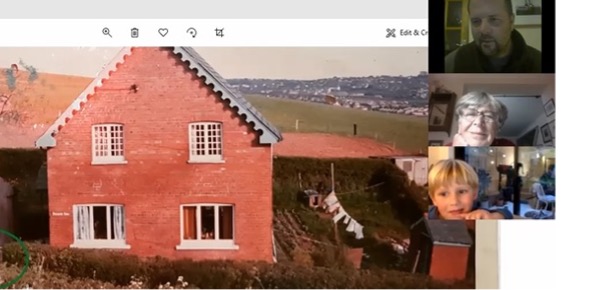

I connected with artist and teacher Dr Simon Woolham; sharing a life course journey through Google Earth – more on https://insearchoftheshortcuts.com. On a subsequent family chat with my Mum and nephew – then aged 3 – we focused on an estate agent photo (dated from 1977) of the house where my brother and I would grow up. The image featured an outdoor toilet, only white clothes on the washing line, and neat rows of vegetables in the garden. As we had been swapping lots of family videos, we agreed to record the conversation as a memory for us all. Part of the experience included drawing on the photo, which helped conversations flow. My nephew loved the tractor in the field behind the house and compared the outside toilet to a campsite that he had recently visited. Altogether it helped me sense how some everyday culture is lost, but how certain things are reinvented and modified.

A short video from our family chat was shared in a workshop at the Swansea Science Festival in October 2020. This was useful in terms of finding out whether the approach could work for people with whom I had no previous connection. After these experiences I decided that recording and editing content from these digital walks of the mind – including the drawings, voices and text that are overlaid – would be something that I aim to develop in any postdoctoral research.

Happily, my postdoctoral project was supported by the ESRC and Wales DTP; I now have scope for up to 5 new digital interviews. The plan is to produce the recorded interviews, including images and conversations, into short films which publicly communicate and examine how spaces from the first three decades after World War II still influence contemporary life.

Developing a digital approach for 2021 and beyond

At present I am preparing an application for ethical approval, with interviews proposed for early 2022. These hour-long conversations would take place on a Swansea University digital meeting platform such as Zoom or Teams. One of the main ethical issues is whether people will be happy for their own image to be used, or whether they would like to be anonymised. Although I hope that people want to appear as themselves, the wider project also has resources to employ performance artists who can turn extracts of verbatim accounts into short monologues.

In the past month I have looked at how other researchers use geography to spark conversations. For example, Amy Barron ran a workshop at the NCRM Methods e-Festival in October 2021. The image above offers questions to ask people about their response to photographs that they have taken whilst outside – more information on Aspect about the Photo go along technique.

Aims for the future

I hope these new interviews can develop a co-produced methodology, which goes beyond traditional sat-down interviews and gives agency to all research participants as the experts of their own biographies. Beyond academia, I also hope that this technique can help generations to facilitate, develop and share their family stories.

Dr Aled Singleton