In this blog, I recount my experiences of conducting online focus groups with young women as part of my Social Science Research Methods MSc dissertation research investigating relationships between Welsh Government education policy and experiences of community participation. Creative activities including mind mapping and zine-making enabled me to more deeply explore participant experiences. I offer some top tips for working with participants using these methods, based on my learning from this experience.

Before starting my ESRC DTP studentship in Social Sciences at Cardiff University, I led a very different life: not working alone in a library, but talking to all sorts of people in public buildings. I worked as a tour guide at the Welsh Parliament and as a workshop facilitator at the National Museum of Wales. These roles sparked my interest in relationships between government, civil society, and everyday life. As a graduate in Social Anthropology, I became increasingly interested on turning the lens on Wales as my own country, as opposed to Aboriginal mythology, or Papua New Guinean rites of passage. I’d also worked as a tutor for home educated children, sparking an interest in learning outside of school and the application of the curriculum to contexts outside of formal education. These experiences culminated in my SSRM dissertation topic, exploring a purpose of the new curriculum for Wales, which is currently being designed and implemented.

This purpose is: ‘Ethical, Informed Citizens of Wales and the World’: Yes, I wrote my whole dissertation around exploring these eight words. I studied how women make meaning of them, and how they might be evident in participants’ discussion of experiences of civil society participation during the pandemic. Having constructed my data, I considered the implications of my findings for Welsh Government policy. My research demonstrated that participants’ meaning-making around the curriculum purpose contradicted elements of policy literature, including government focus on ‘national’ citizenship and the future of the economy. My participants instead drew on a range of contexts for discussing ethical behaviours in community contexts, and used historical examples of discrimination against specific groups to discuss contemporary ‘ethical’ behaviour. ‘Cultural’ citizenship was more prevalent than ‘national’ citizenship, with participants drawing on a range of resources to make meaning of citizenship (Swidler 1986).

Getting Creative

I identified that this kind of research into meaning-making required a qualitative approach (McLeod and Thompson 2009).I wanted to go beyond interviewing, giving participants opportunity to express their experiences in different ways. I had originally wanted to conduct ‘in-person’ focus groups, but like all of us, I was forced by the pandemic to research online. I tried to embrace this opportunity to research in a different way, as my previous research had used good old-fashioned anthropological ethnographic methods. Focus groups enabled me to gain insight into collective views and meanings (Gill et al 2008:291), and acknowledge my active role in creating group discussion for data collection (Morgan 1996:130). This was significant for my feminist approach working with women participants, as feminist approaches prioritise reflexivity (Bozalek and Zembylas 2017:114).

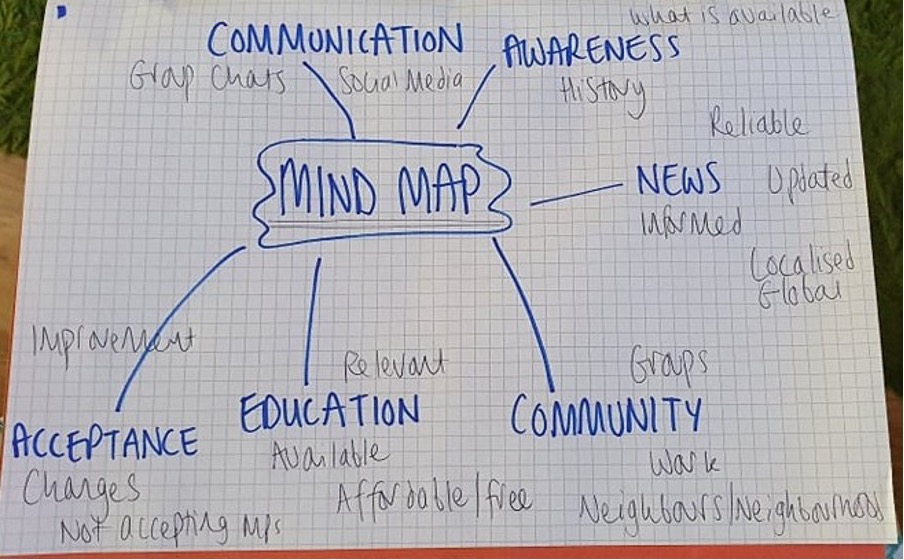

I decided to use creative methods to facilitate focus group discussion (via Zoom) because such multimodal methods can ‘go beyond’ verbal communication, affording deeper insight into experience (Dicks et al 2013:656). Visual methods specifically can be a tool of ‘defamiliarisation’ (Mannay 2010), meaning that this could help participants to think about their experiences in different ways. Specifically, I used mind mapping to explore relationships between concepts within the curriculum purpose. Mind mapping can ‘ aid reflection and individual meaning- making as well as exploring relationships between concepts’ (Wheeldon and Åhlberg 2012). The mind maps enabled me to gain insight into relationships between concepts, such as Christine’s connections between ‘local and global’ through the news: ‘ localised global’.

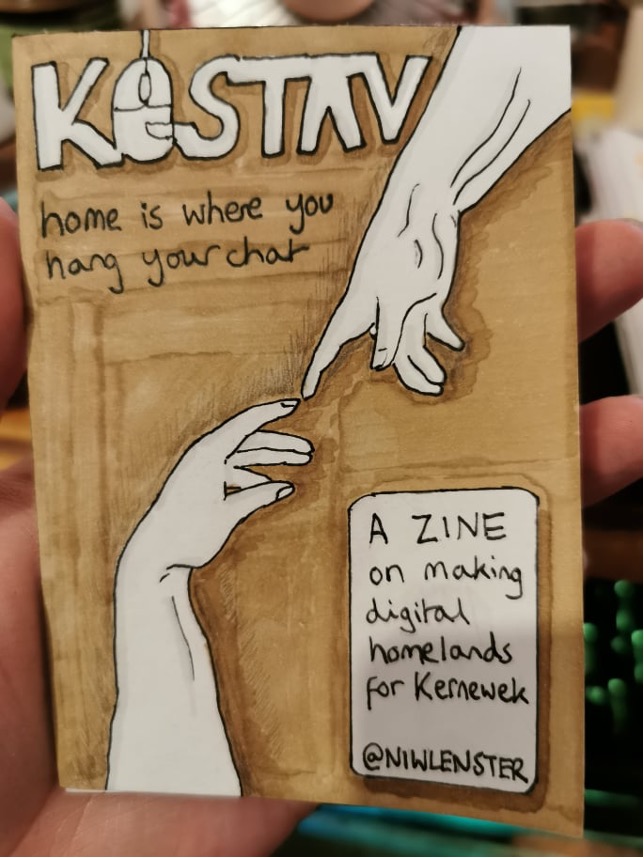

I chose to ask participants to create zines, as zines have potential in identity expression (Gabai 2016) and self-representation (Ramdarshan Bold 2017), and I was interested in exploring the curriculum purpose, which could relate to Welsh identity or citizenship identities. Using zine-making enabled me to gain insight into participants’ experiences. For Lily, online contexts were significant in connecting with her Cornish identity. Discussing her zine revealed that she felt was an ‘ethical’ duty, in terms of preserving a minority language.

Following the focus groups, I used interviews to ‘clarify, extend, qualify or challenge data collected through other methods’ (Gill et al 2008: 293). The interviews uncovered deeper insight into participants’ meaning-making, such as elements of the zines which were the most significant to participants. Rhian drew a sanitary pad to discuss campaigning around period poverty, and the significance of gender equality issues to her community participation.

“And I did one (page) about ending period poverty, because we did a lot of campaigning around that. I’ve drawn a (sanitary) pad.. It’s something that excites me because I don’t think you see that often, as an image. It’s probably my favourite page.”

Rhian, student and gender equality charity volunteer.

So, what did I learn from my experience of facilitating creative workshops online? Using creative methods online worked well in some ways. Participants reported that it enabled them to express themselves freely without pressure from others to draw ‘ well’, and created a relaxed atmosphere. However, some participants struggled with the possibilities of zine-making, which can include poetry, comics, illustrations and more. Some felt that they would have preferred more specific directions. Additionally, of course there were the usual issues around ‘technical difficulties’!

Top Tips

Here are my top tips for getting creative over the internet with young women participants.

1.- Make it simple as possible: don’t overwhelm participants with lots of instructions.

2- Build in flexibility, enabling participation in different ways (take breaks, use different media for creative data construction), but consider how you will balance this with thorough data collection and comparison between participants, if this is part of your analytical strategy.

3- Consider the types of data collection afforded by using Zoom- in the form of screen shots, chat discussions, and so on, not just audio transcripts.

This has been a valuable experience in learning how creative methods can work well online, helping to gain insight into participants’ experiences and meaning making, whilst creating a comfortable atmosphere for participants who may not be familiar with research processes. But, I have also learnt how I would improve this practice going forward, including making the most of the online medium for data collection, and streamlining and simplifying the process to improve accessibility.

Reference list

Bozalek, V. and Zembylas, M. 2017. Diffraction or reflection? Sketching the contours of two methodologies in educational research. International journal of qualitative studies in education: QSE 30(2), pp. 111–127.

Dicks, B., Mason, B., Coffey, A. and Atkinson, P., 2005. Qualitative research and hypermedia: Ethnography for the digital age. Sage.

Gabai, S.2016. Teaching authorship, gender and identity through grrrl zines production. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1909&context=jiws

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E. and Chadwick, B. 2008. Methods of Data Collection in Qualitative research: Interviews and Focus Groups. British Dental Journal 204(6), pp. 291–295.

Mannay, D. 2010. Making the familiar strange: can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative research: QR 10(1), pp. 91–111.

McLeod, J. and Thomson, R., 2009. Researching social change: Qualitative approaches. Sage publications.

Morgan, D.L. 1996. Focus Groups. Annual review of sociology 22(1), pp. 129–152.

Ramdarshan Bold, M. 2017. Why Diverse Zines Matter: A Case Study of the People of Color Zines Project. Publishing research quarterly 33(3), pp. 215–228.

Swidler, A. 1986. Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies. American Sociological Review 51(2), pp. 273–286.

Wheeldon, J. and Ahlberg, M.K., 2012. Mapping mixed-methods research: Theories, models, and measures. Vis Soc Sci Res, 4, pp.113-48.