When I started my collaborative ESRC funded PhD in September 2019, I imagined I’d spend many months traveling for my fieldwork. My research topic looks at nonviolent responses to armed conflict, and civilians protecting themselves and each other without the use of weapons in violent conflict. During the first 6 months of the programme, I planned fieldwork interviews and workshops, as well as participant observations in practitioner conferences. Ethical and security considerations limited where I could travel, but as my project was a collaborative one with an NGO in the civilian protection sector, I was able to make contacts and plans for travel relatively quickly. When travel restrictions were first imposed in March 2020, I naïvely assumed that I could wait it out; spend a few months on my literature review before travelling, as planned, for my in-person fieldwork. By September 2020, I realised this would not be possible, and I’d need to make alternative plans.

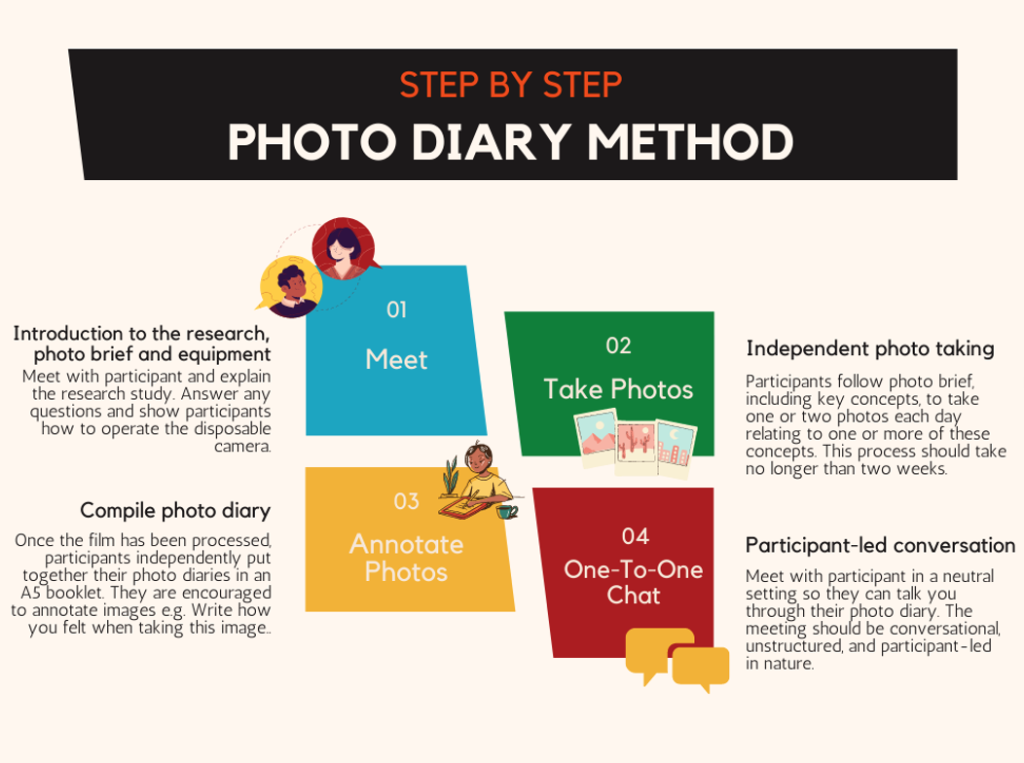

Zoom Interviews and Workshops

Like many other researchers in 2020, I took the decision to move my fieldwork online. While this limited who I would be able to speak to – access to stable internet connections can be tricky in conflict affected areas – I reassured myself that online research could also be an opportunity to reach more people who would either be too busy to meet with me in person, or located in areas I wouldn’t (for financial or ethical reasons) have been able to travel to. I also organised an online workshop with around 20 practitioners, as I was keen to hear conversations between practitioners in a more relaxed environment than one-to-one interviews. While it was relatively easy to schedule this fieldwork (in comparison to face-to-face), there were a number of difficulties of working online this way that I either had not anticipated, or had underestimated.

(Un)social Distancing

Interviews are always tricky, especially when using a qualitative interpretive methodology where I was interested in how people made sense of their work, rather than extracting objective information. Creating a relaxed environment online, I found, was even more difficult. Telling their stories of living and working in armed conflict was an emotional experience for a lot of my participants, and not being able to give them some privacy as I could in a coffee shop by going to order another drink was difficult and felt unnatural. During one interview, the interviewee had a Zoom filter on to hide their background, and I found it very difficult to get them to relax and talk about their own experiences, rather than their organisation. Around 30 minutes in, their dog jumped up onto their lap, which disrupted the background filter so they turned it off. They then showed me around their apartment, and I showed them around mine while we talked about working from home, loneliness, and our fears during the pandemic. When I restarted the interview, the atmosphere had completely changed. They were far more relaxed and conversational, and even went back to previous questions to tell me different stories relating to them.

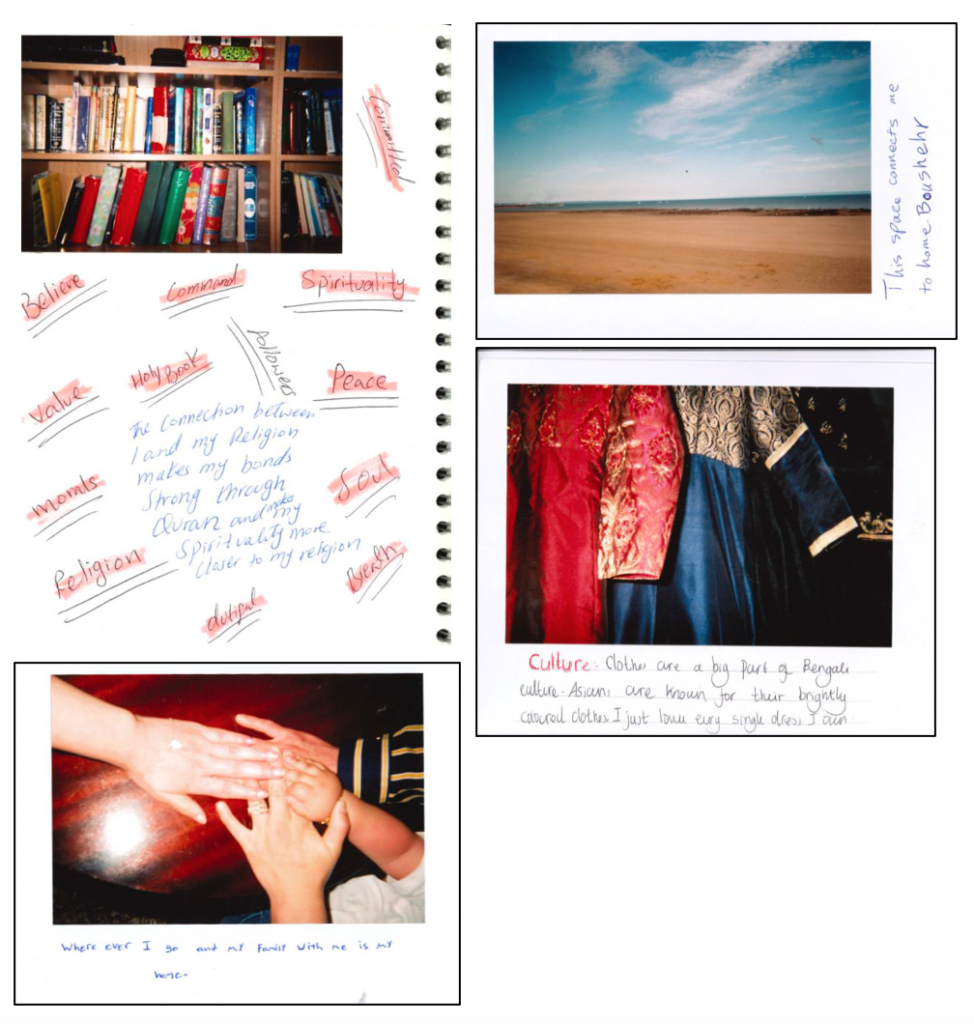

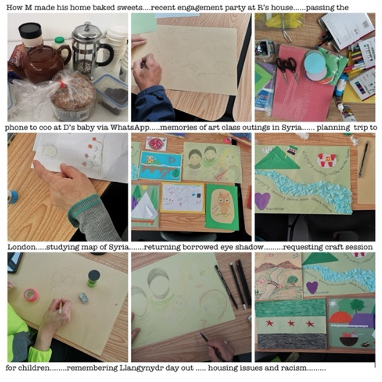

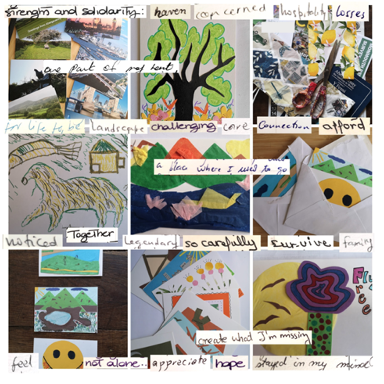

I realised then that being able to create a shared space with people was an important part of building a rapport. From then on, I asked interview and workshop participants to along bring objects or photographs that described how they felt about their work, and to talk me through specific memories they had. While this didn’t fully replicate my being there with them, I learned a lot from how participants would describe their towns and villages, and how the spaces they worked in shaped their imaginations of it. These object allowed research participants to talk around difficult subjects, and to show me what it was often difficult to tell with words.

Other Challenges

Another important (if slightly obvious) challenge of online research is failing internet connections. I spent months carefully planning an online workshop with practitioners in South Sudan – even down the composition of each breakout group. When the time came, however, unstable internet connections across three continents derailed my carefully drawn plan. Participants were leaving groups quicker than I could readd them, and halfway through telling an important story, people’s internet would cut out and they would leave the call. Having research assistant’s there to handle some of the technical issues was a great help, but having to abandon a plan I had spent hours agonising over was scary. I made the decision to only focus on two of the four topic areas I had planned with more time for each discussion. This meant that even with the technical difficulties, groups still had time for some in-depth discussions. I also had participants send me photographs and voice-notes on WhatsApp, which I then shared with the group. While the workshop was stressful for me, it was a shared and often fun experience. It gave me the opportunity to follow up informally with participants, laugh about the technical issues, and have more relaxed conversations.

Top tips for online research:

- Plan: Spending so many hours planning gave me the confidence to be able to think on my feet and improvise, without having to consult my plans and notes, as I’d learned them by heart

- Abandon the plan: While it might seem scary, knowing when to abandon the plan and improvise is important, because you can never foresee every possibility. Some of my best research findings came this way

- Keep a diary: Keep a research diary after every interview/ workshop/ conference/ piece of research you do. I find taking a walk and recording a voice-note on my phone straight after allows me to decompress. Even small reflections that you notice at the time but would usually forget can turn into important ideas if you keep a note of them.

- Ask your participants what they want: While planning my workshop, I had many exchanges with participants about how best to design the session. Taking photographs worked really well for some interview participants, but could be dangerous for others so finding multiple ways for participants to engage (beyond traditional interviews) is more inclusive.

Although my research has definitely turned out differently to how I’d planned it in a pre-Covid world and online research has been a challenge, it has also allowed me to interview participants in many more projects than my initial plan of three case studies. It also gave me the opportunity to get creative in my research methods. After two pandemic years I was used to improvising when things didn’t go quite right in my workshops and that’s something that will be useful in all future research. I’m hoping to follow up with people in person after completing my PhD but I will keep hold of some of my online methods, and always ask people to bring along objects that represent themselves. My research didn’t go as planned, but Covid has taught us that nothing ever does!

You can contact and follow Louise’s PhD journey using the icons below: