Written by Brett Lewis

Brett Lewis is a PhD student at Cardiff University. Currently in his first year, he has a background in economics and politics with an undergraduate degree in Economics from Swansea University, and a Masters in International Political Economy from the University of Warwick. Brett’s research interests are in international relations and the Arctic. Initially brought on by a previous dissertation that examined how the Sino-Russian relationship is made complicated and asymmetric due to the Arctic, Brett’s interest in the Arctic is now on the wider role that it has to play in geopolitics.

This past October I attended the Arctic Circle Assembly hosted in Reykjavik, Iceland. I had two simple missions to complete: experience my first academic conference and begin building my network, and to engage with stakeholders in the Arctic region on the matter of research fatigue and how research design can adapt to meet this challenge.

I can confidently say that the first mission was a roaring success. As an early PhD student, my network mimicked the contact list of a new phone without your old sim in it yet; and thanks to my supervisor it began to populate with experts with years of experience. I heard from a range of research backgrounds, discussed my interests with the best discussants I could have asked for, and I came away with much to think about for my own research.

The second mission was a humbling reminder that I am indeed an early PhD student.

Figure 1: Harpa at night

A World Café on Research Design from Perspectives of Non-Academics

I sought to harvest perspectives on research fatigue from non-academic persons to inform research design, particularly on the subject of Indigenous communities in the Arctic. Research fatigue is big issue for researchers both in attaining sufficient engagement for their research goals and ensuring good quality data. A community that becomes over-researched risks becoming disillusioned with research, losing interest in answering questions on their culture or even developing a negative relationship with research and the researchers that bother them (Kater 2022). Arctic communities are the focus of a great deal of scientific interest, and are therefore at elevated risk for becoming over-researched and symptomatic of research fatigue. The potential causes of research fatigue is a long list: the repetition of research methods gradually decreases interest in engagement (Drake et al. 2023), the lack of noticeable change as a result of engagement and failure to achieve specified research goals (Clark 2008), the mismatch between ethical paradigms of the researcher and the community they research (Mandel 2003), to name a few.

Adapting research design with an awareness of research fatigue can improve the ethical principles and quality of your research. Noticing the colonial underpinnings of research, for example, is a key difference that may improve research outcomes in Indigenous communities (Bartlett et al 2007).

While it was possible to extract the academic coverage on research fatigue quite easily, it would be a great opportunity to speak directly to non-academics at the Arctic Circle Assembly and hear their perspectives. This conference brings together over 2000 people from over 60 countries, some of which include peoples from Indigenous communities, various industries, politicians, people with general interests in Arctic affairs, and of course academics. It would arguably be the best opportunity to meet with direct stakeholders, what with the remote nature of the Arctic and all.

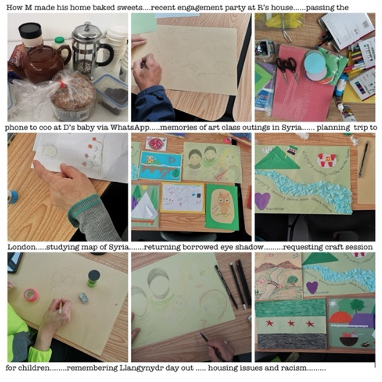

A World Café was the chosen approach to engaging these people. The World Café method is a simple way to get people talking and there is a great deal of guidance on how to carry one out. If you venture over to https://theworldcafe.com you can find extensive guidance, examples, resources, and testimonies about the method. Essentially, the method is designed around 7 guiding principles:

Figure 2: 7 Principles of the World Café

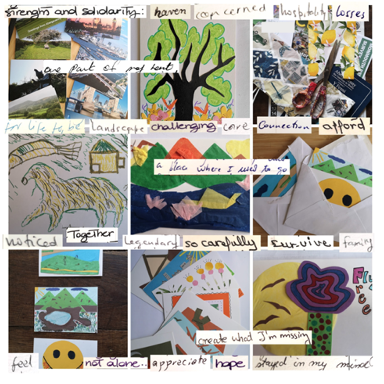

A typical World Café has strict—but flexible to the context—parameters that facilitate highly resourceful discussions on concentrated subjects. Perhaps the most common configuration of a World Café consists of a large room filled with small tables with 3-5 seats at each table. A person is designated as a ‘host’ at each table, which simply means that they do not move from their assigned table, while the other participants will move between tables. The session is structured into rounds, whereby a question is posed to the room to discuss at their respective tables, before another round begins. As the rounds change, this is the point that the non-hosts will move between tables. The final round then ‘harvests’ the conversations had in the previous rounds in a big open group discussion. There is a strictness to a World Café that gives it a rigid structure, but the parameters can vary significantly depending on the context of the session you want to run.

Figure 3: Standard Configuration of a World Café

This was a favourable detail of the World Café that worked for me as I did not manage to get a slot in the conference programme, which would have been the ideal setting as it would have granted me access to a large room, with tables and chairs, and it would have advertised my session to every participant. Fortunately, the conference has meeting rooms that are free to book out for several slots throughout the 3 days of the assembly. This brought about the challenge of adapting my World Café to meet the circumstances which was fairly straightforward. While it was not ideal, the maximum capacity of these rooms was 10, they only had one single table, and I would have to manually recruit participants throughout the conference. So, rather than having the scattered small groups, the intention was to split the table into thirds using tape dividers and to designate the first person clockwise of the divider as the host. Then, it would proceed exactly as a typical World Café would: a question would be posed to the groups for which they would have a 15-minute round to discuss, before the non-hosts migrate to another group and begin the next round.

A World Café is highly configurable to meet the circumstances that you have to deal with. With proper planning, it is conceivable that a session can be hosted in most settings with help of the resources on offer on the World Café website.

Interest is not guaranteed

Despite my best intentions, my adapted plans, and my desire to see the World Café through, it didn’t happen.

I employed simple strategies for recruitment for my session: talk with people during and at the end of sessions that were relevant to my World Café topic, or catch people as they moved between sessions and approach them as they enjoyed coffee and lunch breaks throughout the day. There were a few reasons why this didn’t work:

- Conflicting sessions.

There were over 200 sessions on the programme, and the organisers did an exceptional job of allowing people to attend a diverse range of sessions by allocating a diverse range of sessions in each session slot. If you wanted to attend a session on geopolitics, for example, but also wanted to attend a session on Arctic shipping, you could usually find the option to go to one now and another later. This was not so great for me, as the opportunity cost of attending an organised session with a panel of experts on a topic that was of particular interest to them was usually the more favoured option over my small meeting room, understandably. It was also the case that some people were speakers in conflicting sessions to my slots so it was simply impossible to recruit everyone.

- Sensitivity of the topic.

People were unwilling to attend a session on a subject matter that they considered to be a sensitive or overcovered topic. To some, this matter was sufficiently well discussed and they felt they had nothing to add to the discussion. To others, particularly those closer to Indigenous communities, the topic of research fatigue is a sensitive topic. As previously mentioned, over-researched communities can develop a hostile relationship with research as they feel that their culture is a scientific curiosity to researchers. Where I was asking them to talk about research fatigue with me, a researcher, I was propagating a negative relationship whereby the over-researched community is yet again the subject of more research.

- My ability to persuade people to attend.

It sounded like an easy enough task to ask people to attend a structured session and have them talk to each other for a little while. But I’ve never done this before so how do I go about persuading people to attend a session outside of the programme? With me, a 3rd-week PhD student? Ultimately, this was the single biggest hurdle for which I had not accounted for.

In retrospect, a place on the programme would have made a big difference for the odds of success for my session. While it would not have appealed to everyone, it would have been advertised on an equal standing with other sessions and reduced the part I had to play in recruiting participants.

Working the problem

As it became clear that my World Café was not going to happen, a change in strategy became necessary.

While I could not garner sufficient interest to attend a structured session, I could still engage the same audiences in a different manner. I reverted back to my strategies for recruitment and adapted their purpose away from recruiting to harvesting. Rather than pitching my World Café, I was now talking to them directly with the same exact questions I had intended to use previously. In fact, I had unknowingly been doing this already. When I was attempting to recruit people previously, I was gauging their knowledge on research fatigue, research design, and their awareness of Indigenous communities. By the end of the conference I had spoken to more people than I had hoped to have attend my intended World Café in the first place. As they were more focused conversations, I was able to tailor the questions to meet the circumstances of the moment, be it either to the level of awareness on the subject matter of the person or to allow multiple people to speak when I was engaging multiple people at the same time.

What I had ended up doing was effectively semi-structured interviews. While I lost the structure that the World Café might have provided in ensuring crosspollination of ideas, I gained a flexibility that allowed me to have conversations with people in ways which suited them. It would have been preferable to host a World Café and harvest the result of various crosspollinated conversations, but I still managed to collect relevant data that would have gone amiss without a change in strategy.

A key reflection that made the difference between coming away with something or nothing at all, was that it was prudent to anticipate that I didn’t have infinite time to change strategy. I had booked out various time slots on every day for the World Café, but it was during day 2 of 3 where the time slots that were slipping away from me were what I considered to be my ‘best shot’ of a successful World Café signalled that it was decision time. Rather than pinning all hopes on the slots on the 3rd day (which would have amped up the pressure on myself, too) it was a better use of my time to resort to my new strategy.

One issue still stood out that required further adaptation was the sensitivity on the subject matter that some were wary of. It was not impossible to engage with these people on the issue of research fatigue so long as they were guaranteed the condition of anonymity. This was fundamentally important in gaining trust of these people to allow them to open up on the questions I had. Some, however, did not want to engage whatsoever. Unfortunate as this was for me and my goals it signalled that sometimes the best option is to not engage in research as this is what is in the community’s best interest (Sukarieh and Tannock 2013).

Moving on

Hopefully my experience at the Arctic Circle Assembly has brought some useful tips for when things don’t go the way you had hoped. I find that there is much guidance and information on how to carry out a given method but it is not usually discussed what you should do when the circumstances don’t favour the best case scenario.

The funny thing is that you probably have the skills to adapt to the circumstances already. I reflected greatly on the skills and knowledge I picked up on the SSRM, for example. I thought about what I’ve learned about ethics and was sure to include that in my planned routine when introducing participants to my session, but ended up practicing it anyway with my awareness of anonymity as an option for participants. Rather than the method I wanted to use, I drew on the interview block from the qualitative research methods module to structure my discussions with individuals. I also used my recent dissertation as a springboard to start discussions before moving into research design and research fatigue, which also came in handy with engaging with people with interests in Arctic marine spatial planning and therefore gave me unique insights.

One final reflection is that my supervisor played a key role in supporting me throughout my experience at the assembly. The encouragement and advice he offered kept me steady as I faced the challenges throughout the conference. No man is an island, as they say.

To sum up:

- Sometimes your best-laid plans just don’t work out, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t be adapted to meet the circumstances of the occasion. Spending some time on contingencies will be something I will incorporate into future research excursions.

- The World Café is a solid method for data collection of a diverse range of perspectives. Hopefully next time I’ll have that data to report back on.

- Challenges are to be expected in research. Adapting rather than accepting is much more favourable. Make sure to consult your supervisor when things go wrong, as they are there to support you.

- Learning when not to research sounds counterintuitive, but it is sometimes in the best interest of the participant not to pursue research.

- Building your social skills is—at least in my opinion—as important as knowing the method.

Figure 4: Reykjavik from Harpa

Bibliography

Bartlett et al. 2007. Framework for Aboriginal-guided decolonizing research involving Métis and First Nations persons with diabetes. Social Science & Medicine, (65)11, pp. 2371-2382.

Clark, T. 2008. ‘We’re over-researched here!’: Exploring accounts of research fatigue within qualitative research engagements. Sociology, (42)5, pp. 953-970.

Drake et al. 2023. Bridging Indigenous and Western sciences: Decision points guiding aquatic research and monitoring in Inuit Nunangat. Conservation Science and Practice, (5)8, pp. 1-22.

Kater, I. 2022. Natural and Indigenous sciences: Reflections on an attempt to collaborate. Regional Environmental Change, (22)109, pp. 1-15.

Mandel, J. L. 2003. Negotiating expectation in the field: Gatekeepers, research fatigue and cultural biases. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, (24)2, pp. 198-210.

Sukarieh, M. and Tannock, S. 2013. On the problem of over-researched communities: The case of the Shatila Palestinian Refugee camp in Lebanon. Sociology, (47)3, 494-508.

Figure 1: Harpa at night (Brett Lewis, 2023. Pictures of Iceland).

Figure 2: 7 Principles of the World Café (https://theworldcafe.com Licensed under Creative Commons) Available at https://theworldcafe.com/tools-store/hosting-tool-kit/image-bank/book-images/

Figure 3: Standard Configuration of a World Café (https://theworldcafe.com Licensed under Creative Commons) Available at https://theworldcafe.com/tools-store/hosting-tool-kit/image-bank/book-images/

Figure 4: Reykjavik from Harpa (Brett Lewis, 2023. Pictures of Iceland).